Avant-garde musical savant and Nick Cave’s key creative collaborator, Warren Ellis discusses escape, sanctuary, travel, family and gratitude. Interview by Christian Barker

When we connect with Warren Ellis over Zoom, he’s in his bed in a Toronto hotel room, a few days into Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ ‘The Wild God Tour’ of North America. He apologises for his unkempt appearance, wiry hair and bushranger beard dishevelled, wearing shorts and a battered AC/DC T-shirt.

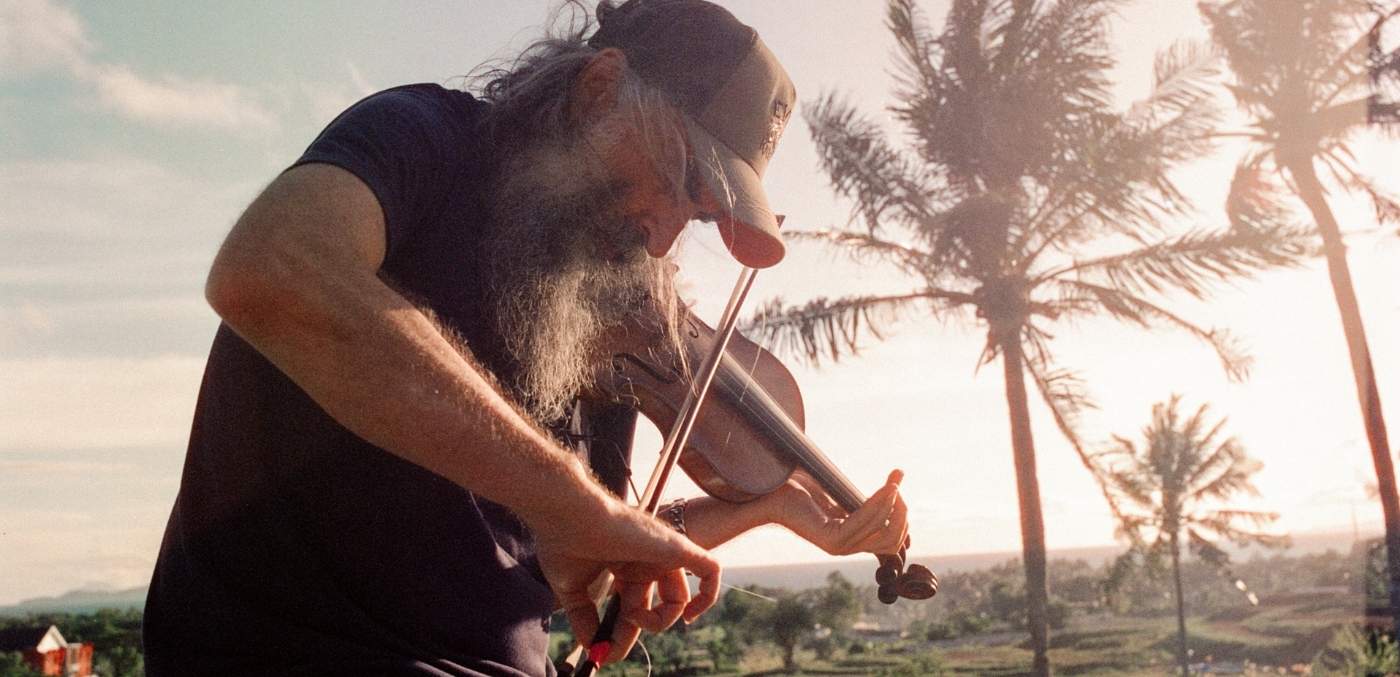

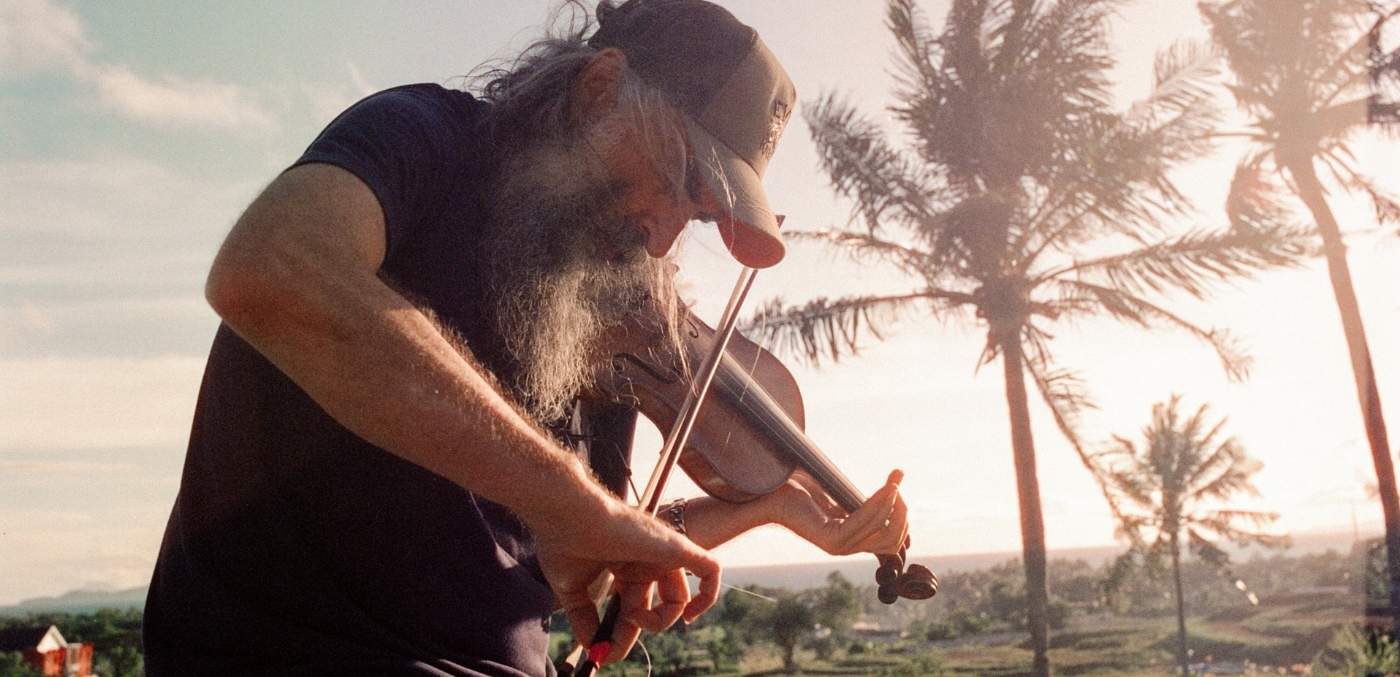

He may not be as mainstream famous as that iconic Aussie rock’n’roll band, but ask any serious sonic connoisseur and they’ll tell you: Ellis is one of Australia’s greatest musical exports. The hirsute 60-year-old multi-instrumentalist (he plays violin, viola, piano, accordion, guitar, bouzouki, mandolin and flute) first broke out in the early 1990s with genre-defying trio, Dirty Three, and has been a core member of Nick Cave’s band The Bad Seeds since 1995.

Over the past two decades Ellis has also worked extensively on film scores, mostly in collaboration with Cave, the duo recently partnering to compose the score for Sam Taylor-Wood’s Amy Winehouse biopic, Back to Black. Now, Ellis has become the subject of a film himself, with the release of Ellis Park. The documentary, a highlight of the 2025 Sydney Film Festival, explores Ellis’s family and small-town background, the genesis of his musical career and years of addiction, as well as his recent support for a wildlife sanctuary in Sumatra, which gives the film its name.

SIGNATURE: Watching Ellis Park, I was moved by the scenes with you and your father, who’s since passed. One moment that stood out was his act of literally packing up his dreams – placing the souvenirs of his early music career into a box and tucking it away in a cupboard, choosing a more practical path, prioritising his family over his passion. Do you feel a profound sense of gratitude for the sacrifices your parents made, allowing you the freedom to pursue a creative life?

WARREN ELLIS: I didn’t really think about things like gratitude until I became a parent. You don’t really understand your own history until you’re looking back on it. So it’s a recent thing, this gratitude. I think it probably started when I wrote my book. [The 2022 memoir, Nina Simone’s Gum.] That’s when I began to understand things, because I had to look at my backstory. I was told I needed to explore why I did what I did – why music was important to me. And I’d never really thought about that before. So yeah, that gratitude you’re talking about… it was there.

But I have to say, when I stepped out with a needle in my arm, a bottle of whiskey, and a violin plugged into an amp, my parents were in no way encouraging me to go down that road. If anything, my dad was… Well, I’d started studying to be a teacher, yeah? And when I didn’t follow through with that, he wasn’t exactly disappointed, but he didn’t understand it. He was like, “I don’t get it – you could’ve had a Volvo.” When I jumped into music, it wasn’t because I thought it was going to go somewhere. I just woke up one day and wasn’t wondering what I was doing with my life anymore. I felt good.

So, were they encouraging? Yeah, in a way. But it wasn’t like my dad thought, “Oh cool, you’re living your dreams.” Far from it. And I wouldn’t expect him to. He came from a very poor background. He started working when he was 15. It would be romanticising it to say he saw it that way. And I wouldn’t expect him to.

But they supported me. They really did. My dad followed me until the end. He always knew where I was playing. He always knew what songs we played at, like, the show in Munich. He was really proud of me. And I think he could see that I’d lived his dream, you know?

“We met on Zoom and in the space of 20 seconds, I knew I was looking at this extraordinary person doing this extraordinary thing. I thought, ‘Okay, I’ll help them’… I never wanted to be public about it”

Having grown up in Ballarat, do you think your experiences – coming from a remote and probably close-minded, insular place, as your recollections in the doco suggest – created a connection with Nick Cave, who had a similar upbringing in the small Victorian town of Warracknabeal?

Yeah, but I think it’s very normal. It’s logical. If you wanted to get out of a small place like that – there weren’t outlets. There wasn’t the internet to see what was going on. No Spotify. You had to dig. And it made you hungry. It made you dream. It fired your imagination. When I first went to England, I didn’t believe it was real until I got there. I wanted to see it. I was like, “Wow, it’s really here.”

I think that’s a very normal story for people who come from rural areas. Some people are happy to stay, but for others, it makes you hungry. Back in the time I’m talking about, when I was a kid, the information coming in was really minimal. So you just had to create a lot in your head. Growing up in the country was great for that – you could just jump on your bike, ride out, and be off the grid real quick. My imagination would just run rampant. We’d be doing wild things – crazy stuff, like playing on old trains and all that. If I thought my kids were doing the same, I’d probably freak out. But

I loved it.

Riding along the line, trucks full of sheep flying past – you just didn’t think about it. You weren’t texting your mum to say where you were. Once you stepped out the door, you were in the world. I really loved that freedom that growing up in a place like Ballarat gave me.

I was in the suburbs there, and I loved that kind of freedom, to just sit and think about stuff, or whatever. I didn’t realise it at the time, but growing up in a town like that…

All that stuff only really made sense looking back at it now – not mentally, but just seeing the points in my life where things shifted. Making this film did that for me, same as writing the book. It made me look at my life in a way I’d never wanted to before.

My work’s always been about the now. The only thing that matters is what’s coming next. I don’t stack up my achievements or sit on my successes. That makes you flabby. I’ve never had that approach, like, “Well, I did the music for Jesse James [The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, 2007], so I guess I can be happy now.” I don’t think like that. This process forced me to look at things, to look at the points in my life where things changed.

You’re based in Paris now, right? That’s where you live when you’re not on tour?

Between Paris and London, yeah.

What is it you love about those cities? What drew you to them – apart from your partner being from France, which

I imagine was a strong pull?

Well, Paris was because I met my girlfriend at the time – we got married, had kids. But honestly, I wanted to live anywhere but Australia. From about 1984 onwards, I just wanted to be anywhere else. You could’ve sent me wherever – I just wanted to be anywhere else. That was just something I went through at the time. I don’t know, man. You just end up in places because life takes you there – if you get out and get into life.

I’m so grateful I was born in Australia, because I think it gave me a foundation to deal with most things. That sense of space, and the sense of possibility – and the desire to get out. That was such a great thing to have. It’s what gets you out of home, away from your parents. You do these things because you’ve got to get out. You’ve got to get away from stuff. I think there was a thing – maybe it was generational. I don’t know how old you are, but I’m 60, and in my age group, there was this thing where we all wanted to get out.

With Dirty Three, we knew we had to find an audience outside of Australia, or we wouldn’t exist. We were just a small, marginal band playing to a few hundred people. We knew they’d get bored – and we’d get bored, too. So we had to get out. And that’s a good way to be – knowing you’ve got to leave. There’s nothing like leaving a city, dude. Nothing like waking up and knowing, “Tomorrow I’ve got to go to Philadelphia.” That’s the great thing about touring. I love that. It shows you how easy it is to just go in and get out. And I’d always had issues with home environments, as you can see in the film. So travelling and getting out – that was something I knew deeply.

On tour, how do you make yourself feel at home when you’re in a different city and a different hotel every night? Or do you not even try to settle in?

Ah, I don’t think about it. I’ve got a suitcase, I’ve got my stuff… I don’t think about trying to feel at home. I’ve got other things to think about. The show. What’s next. I call my kids, and suddenly home is there. I talk to my wife. That’s home, you know?

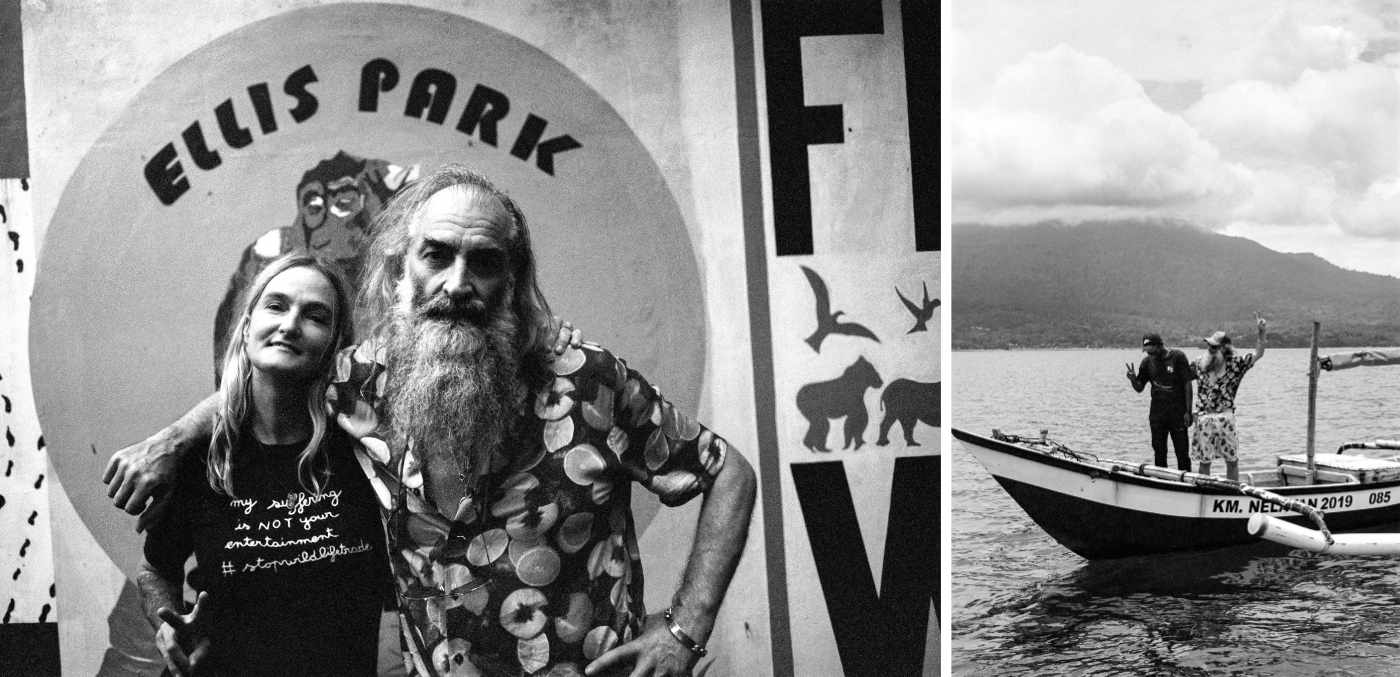

Part of this documentary is about your family and hometown, but its core focus is the great work you’re doing in Sumatra, financially supporting the wildlife sanctuary now named in your honour, Ellis Park. In the film, you mention that you hadn’t even met the founder, Femke den Haas, before you committed to supporting the project. So what drew you to it? What sparked your interest in backing a wildlife reserve caring for animals that have been exploited, abused or smuggled?

Well, I’ve always kind of given to people on the streets and tried to support things, like Médecins Sans Frontières and stuff like that. But with the bigger organisations, you’d always hear that their integrity was questionable, and that the money wasn’t actually all getting to the people who needed it.

So I was looking to donate some money. During COVID, I was supporting orchestras and things like that. I realised I was in a privileged position — I could weather it out, where many couldn’t. Then a friend of mine – Lorinda Jane, who used to book Dirty Three – introduced me to Femke. I’d said I was looking to do something like that, and we met on Zoom. And, well, I say it in the film – in the space of 20 seconds, I just kind of knew I was looking at this extraordinary person doing this extraordinary thing.

At first, I thought, “Okay, I’ll help them get some land.” I figured that would be it. But then I realised we had to build the thing. There wasn’t anything there. It was just a group of people over there, struggling against the elements, struggling financially. It wasn’t some long-held idea I’d been mulling over. I never wanted to be public about it. But eventually, I decided I needed to run it up the flag and see how it went.

Read more:

Waste not, want not: Chef Josh Niland’s radical food philosophy

Formehri: the creative journey of Andrew Doyle

This article originally appeared in volume 51 of Signature Luxury Travel & Style magazine. Subscribe to the latest issue today or be the first to see more exclusive online content by subscribing to the enewsletter below.