Creative journeys rarely come more epic than Andrew Doyle’s. And the Australian style entrepreneur’s globe-spanning mission – to build the finest, and most responsible, knitwear brand in the world – is only just taxiing for takeoff, writes Nick Scott.

A Steinway piano’s warm sonic nuances can be attributed to the close-grained Sitka spruce from which its soundboard is made. A fine leather’s suppleness and tactility come down to its grain and molecular structure. Winemakers would struggle to coax subtle complexities from pinot noir grapes unless they matured slowly, in cooler climes, tenaciously drawing nutrients from limestone-rich soil.

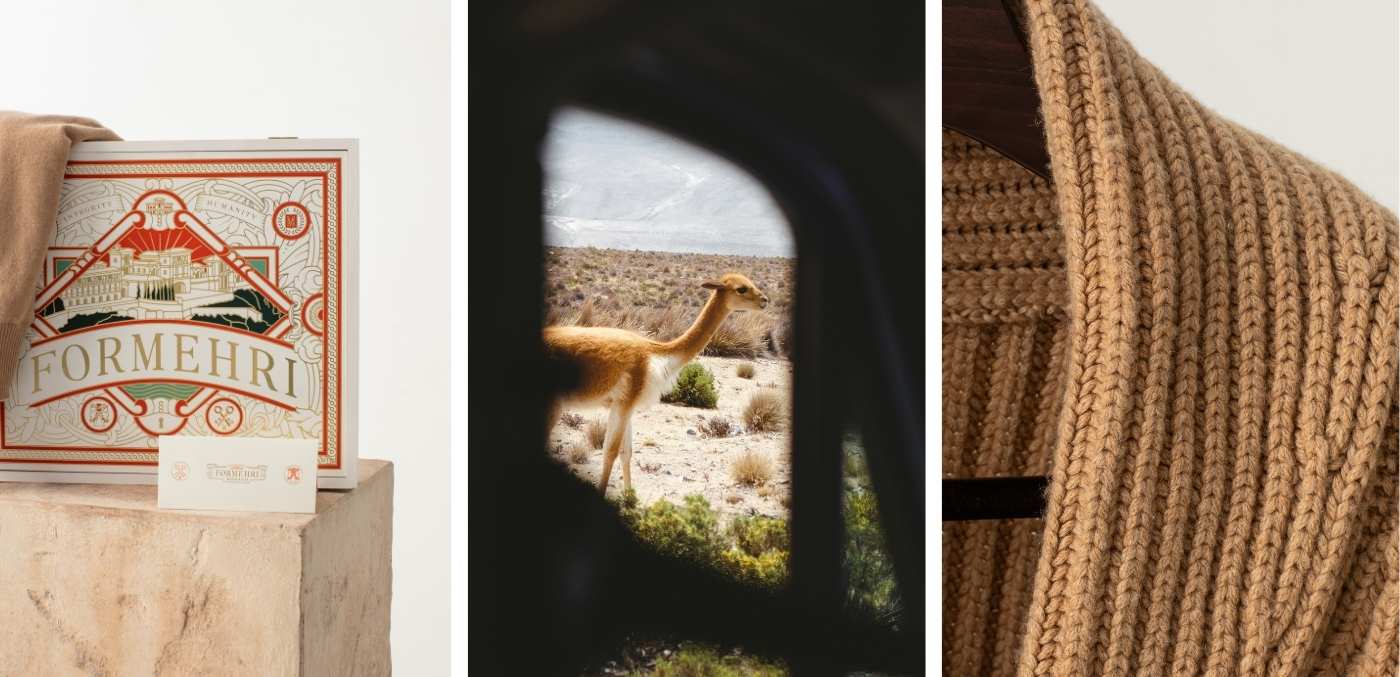

When it comes to the best commodities money can buy, it all starts with the raw material, which, in the case of ultra-luxe knitwear, is obtained from the slender-framed camelids that reside in South America’s central Andes. “Vicuña is the softest wool in the world,” says Andrew Doyle, founder of luxury knitwear maker Formehri. “When you touch it, it feels, compared to cashmere, like cashmere feels compared to sheep’s wool. And it’s insulative; you can wear a lighter-weight knit in vicuña and remain as warm as you would in a thicker gauge of cashmere. It also breathes really well.”

To learn how ultra-luxe garments made from this sublime fibre became Doyle’s life calling, we need to rewind 15 years or so, with Doyle experiencing something of an epiphany. “I’d always been interested in the aesthetics of clothing,” he says, “and then, when I was in my mid-20s, I was in a little book shop one afternoon and there was this pocket-sized book written by [English menswear commentator] Simon Crompton, which was called Le Snob Guide to Tailoring. I read it in an afternoon, and I just felt like I’d found my home. I was like, ‘This is who I am, and what I love.’ It clicked.”

Doyle was building a finance recruitment company in his hometown of Canberra at the time, and while he didn’t give up the day job, so to speak, he did become a devoted menswear autodidact, and for many years shared his ever-broadening repertoire of insights into bespoke tailoring and handcrafted menswear with the world via his own blog, Timeless Man.

As that platform’s name implies, Doyle’s passion is for men’s style codes which are eternal rather than ephemeral (“If you can date what someone’s wearing, to me, that’s not right,” he says). This, along with a passion for artisanal craftsmanship and strong feelings about fast fashion’s gratuitous unsustainability, made him particularly receptive to his second epiphany.

That took place some 13,000km from that dusty Canberra bookseller, on the Uyuni Salt Flats of Bolivia. “I’d just got married, and we were still in that phase of just being able to drop everything and go places,” explains Doyle. Already cognisant of the wonders of vicuña fabric, as he beheld the creatures in their natural habitat, he was curious to find out more. So he arranged – via Meg Lukens Noonan, author of The Coat Route: Craft Luxury & Obsession on the Trail of a $50,000 Coat – to meet representatives of rural vicuña producers.

“I went along just hoping to find out more from the inside, but we found out that these vicuña farming communities are really struggling with poverty, and I thought: ‘Maybe there’s a way that we can help.’” These days, 20 per cent of all Formehri’s profits go to charitable partners, many addressing the health, education and housing needs of the Andean Highland natives, who safeguard the animals from whose soft underbellies the brand’s precious source material is shorn. For now, though, what would become Formehri – and we’ll come back to that intriguing name later – was about to begin its quest. Vicuña wool is confoundingly difficult to come by. Not only do the creatures’ downy inner follicles grow so slowly they can only be harvested once every three years, but the animal is endangered too.

“Vicuña is the softest wool in the world. When you touch it, it feels, compared to cashmere, like cashmere feels compared to sheep’s wool”

While once, millions of vicuña roamed the high Andean regions of Bolivia and Peru, the creatures were nearly obliterated by hunters killing them for their wool and meat. “They were almost completely wiped out,” says Doyle. “They’re slowly regenerating, but it’s illegal to domesticate them. Every year, some communities, with special permission, herd them, put up a temporary fence, clip them, then let them all go again.”

The sourcing of what the Incas once dubbed the ‘wool of the gods’, though, is just the start of a Formehri garment’s journey. “Because it’s such a fine fibre, the challenge all along has been finding the very best experts, wherever they are, to help the best product that could possibly be made,” says Doyle. As such, the shorn fibres’ first port of call is a specialist facility in Bradford, England, for cleaning. “They get shipments from Bolivia – bales of wool clipped straight off the animal; it’s got sticks in it, it’s dirty, it’s greasy. But they have the expertise to clean vicuña without damaging the fibres, and it leaves that factory as this clean, fluffy material you want to dive into.”

Next comes the spinning stage. “Because it’s so delicate, spinning vicuña – converting it from that fluffy cloud of fibres into a cone of yarn – requires knowledge of the correct tension, speed and treatments that only a few mills in the world possess,” says Doyle. The one he found that was up to the task – in Cagli, a rustic hamlet in Le Marche, Central Italy – is also tasked with ensuring critical length of fibres. “Our vicuña is grade 9, which is the finest and longest fibres possible,” says Doyle. “We pay a significant premium for this, but the garments will last much longer and pill less than anything else.”

Knitting takes place in a small, family run workshop in Bologna, which also has a track record in working with delicate fibres. Finally, the knitted pieces take a 400km leap west – the final leg of their journey, before distribution – to Monaco for hand finishing and quality assurance. “It’s a tiny factory that’s been there since the 1950s and specialises in complex handwork techniques – sequins, buttons, buttonholes – and it took me five years to convince them to work with us,” says Doyle with a laugh. “They only worked with Hermès and Chanel before. After five years of saying ‘No’, I think eventually they just realised I wasn’t going away…”

Doyle’s tenacity in his mission is hinted at – nay, spelt out by – the name he has given his brand: a respectful nod to the woman who inspired his creative journey. “My wife, Mehri, once said to me that she’d always dreamed of living in the south of France,” he says. “I took it upon myself to make that happen, and when an opportunity at that factory in Monaco arose, a lightbulb went on again.”

With the youngest of their three children aged just four months, the family moved to Monaco for a few months in late 2022 to finalise logistics; these days Doyle travels back and forth between Sydney and Monaco. “Our goal is to move to Monaco for at least six months each year, and eventually live there full-time,” he says.

Meanwhile, the brand’s much lauded product line, currently made up of crew-neck, V-neck and mock-neck sweaters as well as torso-hugging shawl-neck cardigans, will soon encompass garments in baby cashmere. “The price point will be about half that of our vicuña pieces – plus, vicuña is a rusty colour, so you can only go darker, whereas baby cashmere is white, so we’ll be able to offer a broader colour palette,” he says.

It all seems symbolically apposite, given just how colourful the story of Formehri’s creative journey is – one imbued with romance in all its forms

This article originally appeared in volume 51 of Signature Luxury Travel & Style magazine. Subscribe to the latest issue today.

Read more:

Peruse Chanel’s new Métiers d’Art collection

Pre-loved luxury and its role in sustainable fashion

Are Ray-Ban Meta AI Glasses the new travel essential?